The PoX-4 Bug Hunt

Sep 2, 2025Good testing makes life easier - fewer bugs, smoother releases, less stress when things go live. But what counts as “good enough” testing? Honestly, it’s never good enough. Especially when you’re dealing with critical system infrastructure.

When I worked on Stacks Proof of Transfer (PoX-4) we had to make sure the system would behave correctly not just for individual operations, but for any sequence of operations users might throw at it.

To address this, we built a stateful property testing setup with:

- 20+ command generators covering every possible user interaction

- 20,000 test iterations per session

- 9 different wallet configurations

Why so much? Because smart contracts that coordinate entire networks can’t afford bugs. The cost isn’t just money - it’s network halts, lost trust, and potentially breaking consensus.

The Challenge

PoX-4 is the 4th version of this contract. Many would think by version 4, most bugs would be gone. But this isn’t just any smart contract - it stands at the core of the Stacks blockchain’s consensus mechanism.

The real complexity comes from PoX bridging two blockchains. Every Stacks block gets anchored to Bitcoin, miners transfer Bitcoin to earn mining rights, and STX holders can lock their tokens to earn Bitcoin rewards. All of this has to integrate perfectly together.

Standard testing approaches weren’t enough. Unit and integration tests can check isolated functionalities and sequences of events, but only finite and predefined ones - they can’t verify that random sequences of hundreds of operations maintain system integrity.

The key insight: our setup generates massive sequences of possible events that mirror real-world usage. Out in the wild, users may not always follow predefined test scripts - they perform operations in unpredictable orders that developers might never think to test.

The Stateful Property Testing Setup

Working with Nikos Baxevanis , we used fast-check to build a stateful property testing setup - PR #4550 . The goal was to achieve a fuzzing effect against the PoX-4 contract. Note that back then, no fuzzer for Clarity code existed (though we later built Rendezvous - more on that in a future post).

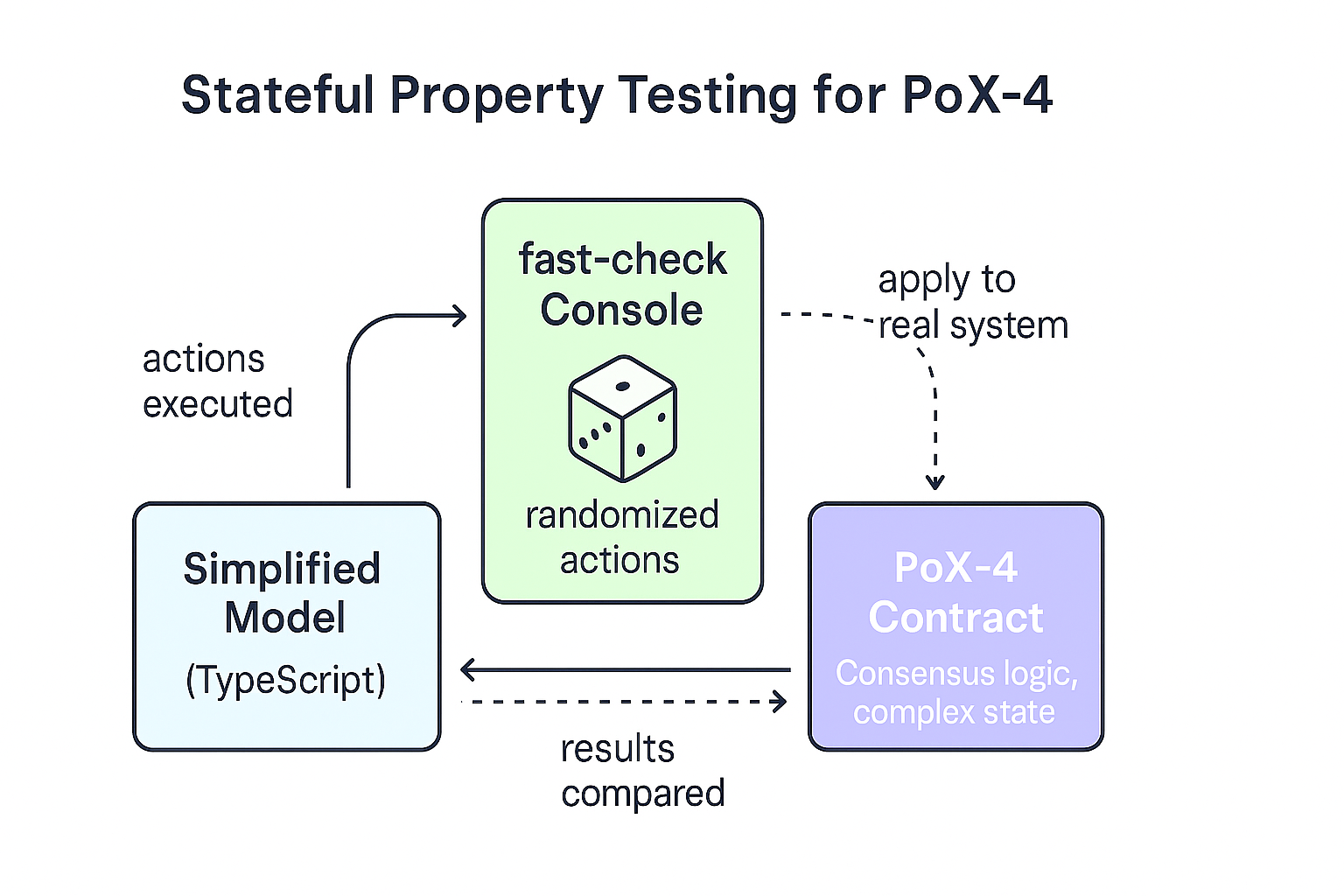

The approach is straightforward. Our testing framework had three moving parts:

- Simplified Model (TypeScript) — a simplified data structure mirroring the main PoX-4 business logic

- fast-check Console — a setup capable of generating thousands of randomized sequences of valid user actions

- PoX-4 Smart Contract (Clarity) — the actual internal state of our System Under Test (SUT)

Each random sequence is applied to both the model and the real contract. If they disagree at any point, we’ve found a bug.

Here’s a visual representation of the testing setup:

Think of it as having a simple calculator alongside a complex computer - both should give the same results, but if they don’t, something’s wrong with the complex system.

Implementation

You can check the setup’s entry point here .

You can surf all possible user actions (commands) here .

Want to give it a try? Here’s how to run it locally:

$ git clone https://github.com/stacks-network/stacks-core.git

$ cd stacks-core/contrib/boot-contracts-stateful-prop-tests/

$ npm install

$ npm run test

Results

Our stateful property testing setup found three subtle but real bugs in PoX-4 - the kinds of edge cases that only surface when users interact with the system in unexpected ways:

- Missing validation in address handling - Issue #4645

- Transaction abort instead of caller-catchable error - PR #4670

- Arithmetic underflow - Issue #4720

Why This Matters

Consensus bugs aren’t like classic app bugs. You can’t just patch and redeploy. Fixes require governance, coordination, and a network-wide rollout — like replacing hardware mid-flight.

Traditional testing checks what you think might happen. Advanced testing techniques check what you don’t think to test. When the stakes are network consensus, you always need more.

What I Learned

- Version 4 doesn’t mean bug-free - complex systems never stop surprising you

- Standard tests check what you expect - property tests find what you don’t

- Time reveals everything - stateful testing shows how systems really behave in the wild